10 Questions for Expectant Moms to Ask BEFORE the Third Trimester

Christina has been a semi-regular guest poster over the years here at KOTH, and I love her posts for several reasons, but the main one is that she is nothing if not well-researched and thorough. Her meaty posts show off her passion for digging deep into hard, controversial issues, and then using that information to empower women to make their own educated decisions. — Stephanie

Guest Post by Christina Szrama

As a new doula, I’ve spent the past year learning a lot through trial and error. I’ve seen many beautiful births—every one of them a true miracle. I’ve watched some birth teams affirm and build up a mom, while others absolutely undermine her confidence and disempower her, even as they add to her suffering.

I’ve realized just how many things you need to have settled with your care provider beforehand as opposed to mentioning it in a birth plan and trusting that it will be honored mid-delivery. Pushing is not a time to argue about pushing position. The doctor who seemed reluctant to “allow” a VBAC “trial of labor” may decide that your baby’s heart rate shows that he “might be distressed,” and you may be whisked away to C-section before you know what’s happening.

In labor, where two lives are involved, we more than ever want to be able to trust our care provider. Having to question or second-guess your doctor or midwife’s medical advice is far from ideal, and, in the worst case, could be life-threatening. Your care provider must be your #1 advocate in your mind, NOT an obstacle to be overcome.

Initiating an active role in preparing for labor and birth

As women, we want to take an active role in our health care and our baby’s health care, so how can we best ensure that our voices are heard, our concerns addressed and our research truly honored? By having good (sometimes long) discussions with our care providers well before the last trimester of pregnancy.

We may find our care provider enthusiastically familiar with anything we mention, or excited to try something new to him but evidence-supported. We may find her taking up our cause with confidence and enthusiasm. Or… unwilling to budge on issues we deem non-negotiable.

In that case, the three last months of our pregnancy should leave us enough time to find a new care provider. (And YES, that is OK!) Or you may reach a compromise you can both agree to.

For example, with my daughter I would have preferred to deliver without any IV whatsoever, and while my midwife agreed this would be fine, she knew it would cause needless consternation at the hospital, so I decided I was OK with the saline lock. I never needed it attached to anything, but it avoided a lot of hassle in my long, drawn-out posterior baby birth!

Image by jewelrylvr

10 questions to ask before your third trimester

In my experience, here are 10 discussions you will want to initiate well before your due date, especially if you desire to have the best chance at an uncomplicated, normal birth:

1. What is your personal C-section rate? Your practice’s? Your hospital’s?

You may well have already asked this as you picked your care provider in the first place. This matters because you don’t want to expect to “beat the odds.” Doctors and midwives are just like anybody else; they tend to do what they always do.

This also gives you insight into how they view labor: if they view labor as a natural, healthy, generally safe part of a natural, healthy, generally safe time in a woman’s life (pregnancy), they will not be in the habit of intervening. However, if they view labor and delivery as a hazard from which many women need to be “saved,” they will intervene regularly and invasively.

The maximum rate of C-sections considered acceptably safe by the World Health Organization (the WHO) is 10-15%. If your care provider’s personal rate is higher than this, switching is probably a good idea. If her practice average is higher, it may also be wise to transfer, since you may well deliver when he/she is not “on-call,” and you don’t want your doctor’s call schedule to be a factor in when you want to give birth.

Lastly, if your hospital has a high C-section rate, you may want to find another option, since that is an indication that “hospital policy” tends to create births that end in C-section.

2. What do you consider to be “post-dates”?

This is another glimpse into a care giver’s perception of birth. A care giver who recognizes that each woman and child can be different and yet still perfectly healthy will likely believe that most babies come on their own when they’re ready. The clinical definition for “post-dates” or “overdue” is 40 weeks from conception, or 42 weeks gestation. Women can safely carry babies far longer than that, with the longest recorded pregnancy lasting 53 weeks 6 days (yes, that is just over a full year!)– mom and baby were both fine.

However, it’s become common in our culture to assign babies a “due date” exactly 40 weeks from a mom’s last menstrual period (LMP), and treat the woman as ill and her baby’s life as threatened every minute over that date. Many care providers commonly induce labor on due dates, and still more will induce by “41 weeks.”

Know that the average first-time Caucasian mother will naturally carry her baby 41 weeks and 1 day, which makes inducing at 41 weeks a bit ridiculous. Second-time moms average 40 weeks 3 days. (I tell all my clients to add a week to their “due date” and get that in their heads instead!) I am not sure of the averages for expectant mamas of differing ethnicities, however, rates DO seem to vary by family, so asking your mom, aunts, grandmas and cousins for their gestation length can be helpful.

Also, not every woman has a 28-day menstrual cycle, and far fewer ovulate exactly on day 14 of their cycle. If your care provider bases “due dates” on known or estimated conception dates rather than LMP, that is another positive sign. If your doctor or midwife operates on a “wait and see” basis, monitoring babies regularly after 40 weeks instead of inducing, this is a very good sign.

Some care providers are constrained by hospital or license to only handle pregnancies lasting up to 42 weeks. (However, even in such a case care providers are required to give patients 30 days to find a new provider after giving a notice of termination of care, which provides ample time for most babies to come.)

3. How do you conduct inductions, and what percentage of your patients do you induce?

This question naturally follows the previous. If a care provider believes pregnancies have to end by a certain date, then they will probably conduct more inductions. Care providers who focus on wellness and nutrition and listen closely to their patients will also often be able to help you avoid situations requiring induction (for example, pre-eclampsia, diabetes, high blood pressure).

However, even the most conservative care provider will likely have a few patients for whom induction is a medical necessity for one reason or another. In those cases, what methods are usually used? While you wouldn’t be able to determine how exactly a potential induction would go (it will vary based on what you and your baby need), a discussion of what a care provider usually does is very eye-opening. Care providers vary widely in which of the following they combine or use:

- Prostaglandins (prostaglandin E2, brand name Cervadil) are often used to soften or “ripen” the cervix, but dosages and administration protocols vary. They don’t seem to change C-section rates, but they do increase the likelihood of uterine over-stimulation;

- Misoprostol (prostaglandin E1, brand name Cytotec) suppositories are at times suggested to begin the process because it is cheap, however, it is not FDA-approved for such usage (in fact its insert warns of grave adverse effects); once inserted it can’t be stopped or countered, and it has terrible risks, including death for mom and/or baby;

- The Foley catheter (a balloon inserted into the cervix) is mechanical rather than chemical, and as such avoids many pitfalls. It seems to be the preferable method of induction, reducing uterine hyper-stimulation without raising infection rates or discomfort levels.

- Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin), is the most common inducing agent, often used after the other three methods or on its own. It causes uterine contractions and has a lot of risk, often causing labor that is harder on baby and mom than natural labor. Some say it interferes with the natural synthesis of oxytocin; however, much of its risk depends on the dosage and schedule of Pitocin. Traditional usage calls for the dosage to be increased every 20 minutes. Inductions where Pitocin is administered in smaller doses over longer periods of time, aiming to imitate natural labor more closely, tend to have fewer complications.

- Artificial rupture of membranes (AROM, ARM, amniotomy or “having your water broken”) is also often a part of (or the beginning of) an induction. This article outlines the function of this bag of waters, and the risks of breaking it. A drawback is that once your water’s broken, there is generally “no going back.”

- Nipple stimulation (either manually or with a pump). Studies do indicate its effectiveness. You also can use it to help avert postpartum hemorrhage – a good fact to know if you ever are in a precipitous birth situation!

- Alternative methods such as herbal tinctures (often blue and black cohosh), evening primrose oil (a natural prostaglandin), castor oil cocktails, acupressure and acupuncture. These generally are used by midwives instead of doctors. Most formulas have been around for centuries and while they may lack randomized controlled studies, they have years of experience behind them. Generally speaking, natural substances such as those in herbs are more easily assimilated by the body without as many side effects or risks as manmade substances. (I have personally experienced the success of blue & black cohosh tinctures taken orally.)

4. How do your patients get nourishment during labor?

Are you going to be asked to get an IV and content yourself with ice chips (or maybe a popsicle if you’re lucky), or will you be encouraged to eat and drink as you feel the need? Many women find an IV pole quite limiting, and those who opt for a saline lock (or “Hep-Lock “– an IV needle inserted but not hooked up to anything– so it’s there in an emergency) often find that painful and restricting since it can’t get wet. (Mine didn’t actually bother me, but I’ve had clients who all but ripped theirs out!) Besides these considerations there are the risks attendant to the IV fluid itself, including fluid overload and an appearance of excess weight loss in the infant (related to decreased breast feeding).

If birth is a normal event, why would a woman need to be restricted in following her body’s cues of hunger or thirst? “Nothing by mouth” (NPO) is standard pre-op procedure. But birth is not a surgery just waiting to happen. Many hospitals are behind the times with their official NPO policy (which dates back to days of opaque general anesthesia masks); if yours is, this may affect how long you wait before going to the hospital (and also the color of your Gatorade should you choose to “sneak” some…). Many care providers will also have their own policies that may contradict the official hospital dictum; I’ve been in many a birth where nurses turned a blind eye to moms chowing down and drinking whatever they liked due to the care provider’s personal policy.

5. How are babies monitored during labor?

While many care providers expect continuous external fetal monitoring (EFM), achieved by wearing a belly band hooked up to a monitor, these tend to give many false alarms without improving outcomes for mom or baby. In fact, they tend to increase unnecessary interventions.

While some units are mobile, many confine moms to or around beds, which has its own set of drawbacks. Evidence points to “intermittent auscultation,” (listening to baby’s heartbeat for 1 minute every 15-30 minutes while feeling mom’s contraction with your hand) being best for both babies and moms. This is not the same as intermittent external fetal monitoring. This mom’s story provides excellent tips for how to ensure you get this care.

6. What does labor generally “look like” in your practice?

If your care provider will come to your house, when will they come? Will they stay the whole time? Who else will be there? If you will meet them somewhere, what is the protocol for that (many birthing centers aren’t staffed around the clock, so you’ll need to call first after certain hours)? If your care provider delivers at a hospital, how will they be notified? Are they ever not “on call”? What is the hospital’s admission process? (Side note: In my experience, it doesn’t matter how much paperwork you fill out before hand, you will STILL be asked what feels like 100 questions during admission, unless you arrive pushing.)

Once you’re situated, will you be encouraged to move around as you feel the urge, or will you be expected (forced?) to stay in a bed? How often will you be “checked”? Will benchmarks be time-limited (for example, C-section 24 hours after water breaking, or pitocin augmentation if you haven’t dilated to 4 cm in ___hrs)?

Interestingly, ACOG has just extended all of its “normal time limits” regarding labor. Again, your care provider’s normative practice reveals how they view labor; either as “a condition” needing to be “managed,” or a natural process that looks different from one individual to another, but generally sorts itself out.

7. What types of pain management will I have access to?

Many women assume that labor will be painful, and certainly most hospitals reinforce this image. I’ve intercepted several anesthesia teams coming to “evaluate mom’s pain level” before the she even made it out of triage!

While I’m the first to admit that for most women, labor IS hard, uncomfortable work- and at certain points even VERY painful- this doesn’t define labor by any means. Even if we describe labor as “intense” or “hard,” women will want to have their labor eased.

What means will be available to you? Are your only options to “grit your teeth and she-woman it out” or numb all sensation from the waist down (with an epidural)? Or does your care provider encourage bringing a doula, maintaining a calm, positive environment, using position changes and rhythmic movement to manage contractions?

Will you have access to water in the form of tub, shower, or deep pool? Does your provider use a TENS machine, saline water injections, acupressure or acupuncture? Is he or she familiar with hypnobirthing?

Will even simple measures such as a heated rice sock be permitted? (I know one of our local hospitals claims they are a burn risk and some of the nurses won’t “allow” them.) What about other drugs besides an epidural (IV opiates, narcotics, laughing gas)?

How familiar will the support staff (assistants, residents, nurses) be with these things? If you will be doing something rather unfamiliar for your hospital, you will want to make sure that your care provider is 100 percent on board, as well as your entire birth team (husband, mom, doula, etc.).

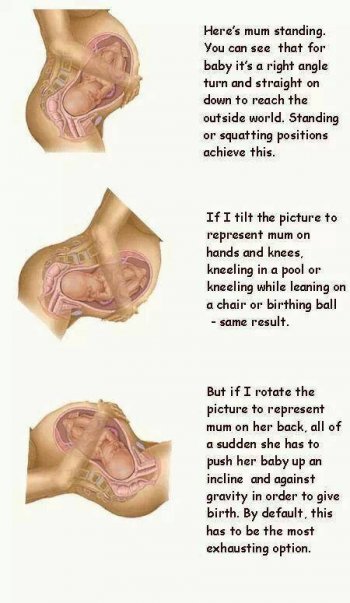

8. Let’s talk second stage labor, aka pushing. How familiar are you with non-supine (“non-prone”) pushing positions? How familiar are you with self-directed pushing?

I think this is the conversation women tend to forget to have… and then really regret skipping!

At two births in a row, at two separate hospitals, I heard two OBs say nearly the exact same words: “well, you can try to push in any position you want, but in my experience, the lithomy position (flat on your back) leaves the most room for the baby.” I bit my tongue and resisted asking these doctors when they last looked at a model of a human pelvis. Further conversation with the same doctors revealed that they’d only ever assisted women delivering on their backs, so their ability to compare it to another position was rather inhibited!

Needless to say, most doctors do not regularly see women pushing any way but with their feet up in stirrups with a spotlight giving them (the doctor) a prime seat , however plenty of evidence (and common sense) point to many other positions being more effective. Ask your doctor how familiar she or he is with alternative pushing positions. If the answer is “not really done it,” then give him or her some literature on the topic. Keep up the conversation until you are certain that she or he will support you on this issue during birth.

While you’re on the pushing topic, broach the subject of self-directed pushing. Many nurses are still trained to count (loudly) to ten, instructing moms to hold their breaths, close their mouths and bear down for the full ten count, breathe in, then repeat twice more with each pushing contraction, and many care providers will let nurses “do their thing.” Known as “purple pushing,” this approach has many problems, including limiting oxygen to the baby, not allowing the baby to stretch the perineum slowly (leading to more perineal trauma), tiring Mom, and generally creating a stressful atmosphere. Since this is the norm, discussions with your care provider need to include when directed pushing might be imposed.

In my experience, far too many women are “allowed to try it their way” for a grand total of one or two pushes immediately upon reaching 10 cm dilation, are told “nope, not working,” and then are rushed on to “the normal way.” Expect the first few pushes to be practice pushes, especially for a first-time mom who has never done this before. Also, so long as baby and mom are fine, there is no need to rush second stage labor. One of my favorite sayings for the pushing phase is, “Don’t just do something, stand there!”

Interestingly, “laboring down” is becoming common for moms with epidurals; essentially moms are encouraged to rest when they get to 10 cm instead of being “pushed” to push, as they formerly were. The logic is that the uterus needs time to contract down around the baby once the baby has moved down into the birth canal, to allow it to push effectively. Contractions have been focused until now on dilating the cervix. Now contractions aim to push baby down and out. Once the uterus is tight around baby again, the “fetal ejection” or “spontaneous birth reflex” will engage: that feeling that you are pushing and no one could stop you even if you wanted them to!

Moms without epidurals can use this new trend to accommodate what’s often called a “rest and be thankful” phase: there is no need to immediately begin pushing if you don’t feel an urge to do so; it may work well for you to just rest and wait until the urge becomes unstoppable and your body begins pushing on its own!

(In retrospect, there have been several births where it would have been better for me to not immediately alert the nurses that the mom was “feeling a little pushy.” The moms had a long way to go yet! Rather, it would have served everyone better for mom to be allowed to just be for a while. If your hospital tends to needlessly rush second stage, this is a strategy that might serve you as well.)

One note on shoulder dystocia (baby’s body getting “stuck” after its head is born): women with a history of big babies or previous shoulder dystocia may want to ask their care provider how they typically handle them. The Gaskin maneuver (having mom flip over onto hands and knees if she’s on her back) is non-invasive and extremely effective.

The summary for second stage labor could be: God has made our bodies well. If we let them do what they tell us they need to do, we will be well served!

9. What is your policy regarding cord clamping?

Delayed cord clamping (DCC) is receiving a lot of good press lately, which means most care providers are willing to accommodate birth plans that include it. However, many care providers mistakenly assume that an intact cord will drain the baby of blood unless baby is kept lower than the placenta. This means some moms have to choose between immediate skin-to-skin and delayed cord clamping. (Sadly, I was at one birth where the doctor flat-out refused to delay cord clamping despite having previously agreed to it in her birth plan because mom was already reaching to hold her baby.) Make sure this isn’t a misperception your care provider has.

In every study measuring benefits of DCC, location of baby has NOT been a factor. Specifically bring up the topic of DCC with immediate skin-to-skin. (This article is a wonderful resource on common questions and misperceptions of cord-clamping.)

As far as how long to delay clamping, even just waiting 30 seconds has benefit. One minute allows 75 percent of the baby’s blood to transfer; waiting 2-3 minutes allows 90 percent. Ten minutes is a great (though arbitrary) number; it also forces everyone to slow down and let mom and baby just be. And there is no drawback to letting the cord remain unclamped until the placenta is delivered.

(In my experience, if your care provider is unfamiliar with DCC, a set time (such as 5 minutes) is more helpful than a vague “until the cord stops pulsing.” It also may be helpful to specify that you mean 5 minutes to clamping, not cutting.)

10. What is your policy during 3rd stage labor?

If you don’t have this conversation prior to birth, you will certainly never have it. “Third stage” refers to the contractions following the baby’s birth that expel the now-empty placenta and begin returning your uterus to its pre-stretched size and shape.

Once that baby is in your arms, you will not be thinking about anything else! Here again, the norm for most hospitals is “active management.” This involves traction (gentle pulling) on the cord to pull the placenta out more quickly and IV pitocin (synthetic oxytocin) or other uterotonic to encourage harder contractions to avoid hemorrhage (some use Cytotec).

The “physiological approach” will tend to let the woman’s body detach the placenta at its own pace (which can lower the risk of hemorrhage), encourage protective maternal hormones to flow through keeping mom and baby together, and allow the natural oxytocin triggered by baby suckling cause contractions.

Many proponents of active management point to studies that suggest it lowers postpartum blood loss (not hemorrhage, just amounts within normal ranges); however opponents argue that too little blood loss can be as problematic as too much. Women in clinical trials with active management were more likely to return to the hospital for abnormal bleeding after discharge in addition to having higher blood pressure, more severe afterpains, and increased vomiting. Their babies were also more likely to have lower birth weights. Lastly, some midwives use herbs and prenatal nutrition first instead of drugs to avoid hemorrhage.

Here again, your practitioner’s view of birth – as a healthy, intricate process that generally functions flawlessly, or a hazardous ordeal which is just waiting to go catastrophically wrong – will affect how they handle the third stage of labor.

Image credit

Recommended Resource

For any mom who would like to do further research on any of these topics, I heartily recommend Henci Goer’s work, Optimal Care in Childbirth. It is quite comprehensive and technical, well-referenced and covers every aspect of maternity care. It might just be the perfect thank you gift for your care provider, too!

Other Posts About Preparing for Birth

Healthy, Natural Pregnancy: Preparing for Labor

How to Have Natural Childbirth in the Hospital

OB or Midwife: Finding the Birth Provider that Works for You

A Comparison of Birthing Settings: Home, Hospital and Birthing Center Births

1o Decisions for Parents of Newborns

Healthy, Natural Pregnancy: Considering Homebirth

For moms that have already had a baby, what do you wish you had asked or known before third trimester?

**I am a doula, but not a doctor. This is based on my own research and how I use it in my own practice. If you have any medical conditions or concerns, please see your doctor.**

Excellent article! I think it’s great to have someone like a doula in your corner when birthing. One thing I wish I had asked is what the incidence of postpartum prolapse/incontinence/pelvic floor dysfunction were and how that would be addressed. I had some issues after my first birth but really didn’t know what was normal or if I should be concerned. The sad thing is, I’m a PT (though didn’t know much about women’s health at the time). So I know that it’s just not a topic a lot of women talk about or even think to ask about. I hope other women will think and ask about the possibility of these issues because incidence is high (estimated 50%+) and you don’t have to suffer in silence. A good pelvic floor/core program from a women’s health PT works wonders!

Thanks, Angela! Have you read this article? http://breakingmuscle.com/womens-fitness/stop-doing-kegels-real-pelvic-floor-advice-for-women-and-men As a PT and a pelvic floor injury “survivor,” I’d love to hear your take on that POV!

I think a better question with regards to c-sections is what is their rate of c-sections for first time moms. The rate of c/s for first time mom’s is around 12% for a national average and the rest are repeat c-sections. But a mom also needs to take into consideration what population a hospital is serving. It would most definitely factor into c-section rates (does the hospital specialize in high risk deliveries? if so, their c-section rate would and should be higher). For me, I increased my doctor’s rates of c-section… my first son died and had to be resus’d after a severe shoulder dystocia (with a lifelong birth injury… this was homebirth) and then I found my doctor and because my risk of s/d was so high again and through a series of events we decided to have c-section for the last 3 babies. Were they needed? yes! Did his rates of c/s go up? Yes and good thing!

As far as post-dates… risks of stillborn increases with each week a woman is pregnant past 40 weeks. Many doctors have seen stillborn at 41 and 2 days gestation and have seen the devastation it causes and that’s why they are so adament about only going to 41 weeks. There are risk and they should not be discounted.

#5… external fetal monitoring has been proven to decrease HIE rates so they definitely have improved outcomes for babies.

#8… most of our bodies will do fine in labor and delivery. to make such sweeping generalizations of if we trust enough it will serve us well though, does not serve us well. To have the mentality of “nothing will happen to me” only strengthens the shock of something not going as planned. I think it’s important to not trust our bodies, but to trust God. Nature can fail, it is fallen because of sin. God does not fail. To be open to whatever happens (some of us do have lemon pelvis’; have you ever seen the illustration of the 4 or 5 different pelvis shapes?). My son was a severe shoulder dystocia (not resolved by anything other than pulling the baby out and snapping nerves from his spinal column)… I thought if I did everything “right” (homebirth with a midwife, all natural, herbs and teas, etc) I’d be above complications. It’s important to remember that things do happen and by God’s grace we have healthy babies… and that is most important.

Thanks for reading & responding! I love a good conversation!! 🙂 But, I think you are mistaking my point– I am in no way trying to say how labor “should” go, nor how to acheive a perfect labor. My goal is to help moms desiring a natural birth to get on the same page with their care provider, so that they will have no regrets afterwards, and especially so that in the case of a complication, women will be able to trust their care provider to make needed decisions instead of second guessing them. If you know your care prvider is your ally, if they say “we need to do__,” you’ll know you likely actually do need it.

As far as continuous external fetal monitoring being proven to reduce anything, you are mistaken. Don’t take my word for it, though; follow the links I’ve posted & read the research yourself! While EFM may be helpful in certain situations (such as a birth involving pitocin)– it is by no means best for baby and mom across the board. We don’t merely want healthy babies; we want healthy babies AND mamas.

I think your statistic on the rate of c-sections for first time mothers, is a bit off? Do you have a source that you culd cite where you found that statistic? I just finished reading the CDC’s latest report on Primary c-section rates, which was published in January of this year. Here is a snippet from their summary:

“The primary cesarean delivery rate for the 38 states, District of Columbia, and New York City that were using the revised certificate by January 1, 2012, was 21.5%. State-specific rates ranged from 12.5% (Utah) to 26.9% (Florida and Louisiana).”

So maybe if you are in Utah, the rate is around 12%? But the national average is nowhere near that. Here is a link to the paper if you are interested in reading more: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr63/nvsr63_01.pdf

Sorry you had misinformation, but C-section is wrong. It doesn’t mean other people can learn better ways than you had.

Read Nourishing Tradions book by Sally Fallon!

These are questions I wish I had asked my Ob! My youngest son is 5 weeks old, and although it was my second delivery I wasn’t prepared for how awful it would be. I don’t know anyone who has ever had a baby anywhere other than a hospital, so that’s what I did for both my boys’ births. I was induced at 40 weeks and given Pitocin, poked and prodded, my water broken for me–it was HORRIBLE. No one was intentionally mean to me, of course, but I felt bullied and terrorized the whole time. Everyone was so BOSSY! They kept telling me what I would or would not do, even when my body was desperate to do something different. After my son was born and I was settled in a recovery room I told my Mom I would honestly have been better off going into the woods and having the baby by myself. We were both healthy, thank goodness, but I felt very traumatized by the whole experience. Next time I’m going to explore other, more gentle options.

Excellent, excellent article! I have asked some of those questions, but you brought up so many that I haven’t. We are expecting our 6th baby this fall. This is my first pregnancy to be seeing a nurse/midwife who delivers in the hospital. I have gone past my “due date” with my last two babies (12 days with our 4th and 9 with our 5th), both times I have been pushed to induce by the doctor. With our 4th I ended up going into labor on my own, but with our 5th, the doctor broke my water. I am definitely going to be asking a lot of these questions. Thank you for such a thorough post!

My husband and I are still in the trying to get pregnant stage. Even though I’m not there yet, I found this extremely helpful and easy to understand. Thank you for writing it. I saved it for myself for later so that I can go back and review it when the time comes.

You are welcome! Thanks for the encouragement! 🙂

As a family physician who provides low-risk obstetrical care (including deliveries) to my patients, I feel both hot and cold about your article. I think the questions you propose for women to ask are thoughtful and appropriate in gauging a provider’s habits. As a health care provider, and as a mother, I strongly believe in birth being a natural and beautiful process, which most often is best served by minimal intervention. Personally, I delivered both of my children naturally, without epidurals or IVs. I have supported many patients in achieving this same goal, when it is their wish.

I agree that there is a general trend toward the “medicalization” of labour and birth in North American society. However, as a obstetrical provider I resent the general undertone of your article that physicians are the sole culprit for this more interventional approach. I agree that some health providers do contribute to the increasing c-section and intervention rates by overusing induction, external fetal monitoring (EFM) and early/forced pushing, as well as other practices that you haven’t mentioned. However, it is my experience, both as a physician and as a patient, that there are many wonderful providers (including obstetricians, family physicians and midwives – all of whom I work with) who work with and advocate for their patients to achieve their birth goals in a safe and natural way.

Of course I support the idea that patients should be able to ask questions of and about their provider in order to make fully informed decisions about their pregnancy, labour and birth. But in encouraging the questions needed to make these decisions, you have given only negative examples of physicians. In the articles of yours that I have read, I haven’t seen even one anecdote of a positive/natural experience involving a doctor. Given my own experience as an obstetrical provider I find it hard to believe that you have not a single example involving a physician that is positive.

Please don’t continually use only examples paint physicians as interventionalists who have some hidden agenda that involves more c-sections or vacuum deliveries. For the vast majority of us, this is the farthest from the truth and painting us in this light breeds mistrust at a time in a woman’s life when trust in those caring for her is so very important. Of course the negative examples exist and should be discussed and questioned…but so too should we celebrate the great examples of teamwork in the delivery room and beautiful, natural birth.

To patients, I encourage you to use the questions listed in this article, as I do believe they are appropriate and useful in making the important decision about who cares for your pregnancy, labour and birth. But I also reassure you that, in my experience, the vast majority of providers want exactly what you want – the healthiest outcome for you and your baby – and that many of us also hope to accomplish this in the most natural way possible.

Hey Julie– thanks for reading! I’m so glad to hear that you are a physician who aims to assist women at doing what they’re usually great at doing– birth babies! I’m sorry to hear that you got a negative vibe from this article; I intentionally tried to use the term “care provider,” to include midwives of all types (CNM, CPM, LM), family doctors (both MD & DO), and OBs, because I know that great care providers exist in all of those fields. My whole assumption in writing this list is that care providers who, as you said, will “work with and advocate for their patients to achieve their birth goals in a safe and natural way,” DO exist! Originally, my “second stage labor” question also had an anecdote from my favorite local doctor (like you, a family doctor with obstetrics) coaching a resident on how to catch a baby from a hands-and-knees pushing position, but I removed it for sake of flow & length. So far in my doula career, most of my births have been OB-assisted, so most of my personal anecdotes, good and bad, feature an OB. 🙂

I do assume that the vast majority of birth professionals (apart from home birth or birth center midwives) will mostly see and assist at medicalized births– that’s just plain statistics– so it stands to reason to expect that most habits and practices are going to be assuming women in those situations. That’s not saying hospital-based staff aren’t wanting natural births, it’s just saying that their norm is more than likely medicalized birth, and as a birth professional, I’ve seen how helpful it is to be clear that you’ll need to be treated a bit differently… far too many moms (especially first-time moms) just assume they know how labor will look, find they are mistaken, in the moment they can’t or won’t argue, and then have regrets. This post is merely aimed to help head off those kinds of disappointments.

Well, wish I’d known about Cytotec before being administered it several times in the hospital (and ending up with all sorts of interventions and a c-section…on the sunny side, baby is healthy). If it’s not approved for inducing labor, how can they use it? Shouldn’t they at least tell you?

Nikolia, you would think so! I’m not sure if you had to sign a consent form that had all the risks outlined in it, in which case it may have been there. The use of Cytotec “off-label” is so common that ACOG has defended it (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12867908). Why is it popular among doctors when even “appropriate” usage can be catastrophic? One OB put it; “The best part about it is that you can block-schedule your nurses so that you have enough on hand… that’s helped our hospital tremendously. And Cytotec is a great agent. It works very, very efficiently… and it’s ungodly inexpensive: 27 cents per tablet.” (Ob. Gyn News 2004, quoted in Optimal Care in Childbirth, by Henci Goer, p 155) Basically it’s cheap and convenient. As the authors of Optimal Care in Childbirth put it, “We do not find this justification over other, safer, equally effective options compelling, and if women were informed of this rationale– as is their right– we think they would agree.” (Goer, p. 155)

This article was very helpful in clearing many doubts I had about the third trimester. Thanks for the article. Also, I came across a really useful website whattoexpect.com which talks about pregnancy and babies. Hope this helps your readers too.

I attempted to push in a side lying position and baby wasn’t budging , laying on my back did the trick. Just saying the position does work for some women, though I believe women should get a choice and a voice in the matter.

Before deciding to go to the hospital I had been seeing a midwife for prenatal care who was actively pressuring me to not attempt to push on my Back (despite having given birth twice in this position before ). With her it felt like rather than me having options it was more her wanting to do the opposite of what hospital do…. glad that I fired her.

I’m curious how active management of the third stage would lead to a lower birth weight baby?